Kaileigh McCrea, Privacy Engineer • 5 minute read

Does Your Cookie Banner Use This Dark Pattern?

Confiant is always on the lookout for security and compliance issues which could be potential risks for publishers. Privacy compliance is a particularly challenging issue for publishers, who have primary responsibility for ensuring any user tracking is consistent with regulations like GDPR and CCPA. Recently I noticed something very odd when analyzing consent string data from the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF), the method devised by the IAB Europe and IAB Tech Lab to help entities in the digital advertising ecosystem comply with GDPR requirements. Under the GDPR, a vendor is required to have a legal basis to track users, typically either user Consent or a Legitimate Interest. Some of the consent strings in the sample had no Consent values at all but had all of the Legitimate Interest values set to true. This raised a few questions: were users really engaging with cookie banners to withhold consent to track but deliberately not exercising their right to object to Legitimate Interest? If you don’t want to be tracked and understand the concept of Legitimate Interest, wouldn’t you reject both? Were these actually malformed consent strings?

Investigation

I was surprised when my investigation turned up a dark pattern in the Consent Management Platform (CMP) configurations being used by several publishers, that may mislead users to believe all data collection has already been rejected, and thus cause them to unintentionally fail to object to vendors’ Legitimate Interest declarations. CMPs provide the interface design responsible for informing visitors about data collection on a site, collecting their consent or rejections, and transmitting those selections to the publisher and vendors operating on the page, usually in the form of a consent string. The dark pattern we found causes a disconnect between what the user might think they selected in the user interface (UI) and what is actually recorded in the consent string, which could sow distrust and damage the publisher's relationship with the user. This pattern, if the user follows the expected path and saves and exits without making any changes, leads to odd consent strings like this one (ellipses indicate where I truncated the string for space and clarity):

{"core": {..."vendorConsents": {},... "purposeConsents": {}, ..."vendorLegitimateInterests": {"8": true, "11": true, "14": true, "15": true, ...}, "purposeLegitimateInterests": {"2": true, "3": true, "4": true, "5": true, "6": true, "7": true, "8": true, "9": true, "10": true}}...}

The "purposeConsents" and "vendorConsents" dictionaries are curiously left empty, but the "purposeLegitimateInterests" and "vendorLegitimateInterests" dictionaries are full. These dictionaries represent, as their names suggest, whether consent has been given for a specific tracking purpose and whether consent has been given to a vendor to track. It should be noted that this string format is the result of decoding the TCF v2 consent string using the standard library, where false values are not displayed but are instead not present in the string at all. This format makes it difficult to determine from the consent string alone whether the purposes or vendors were explicitly rejected by the user or were never shown to them in the first place, or whether the dictionaries are empty due to a bug at some part of the collection process. This ambiguity, and the possibility of some kind of bug Confiant would want to make the publishers and CMPs aware of as soon as possible, is what led me to investigate this process in the first place.

I traced these strings back to the pages they originated from and simulated a user located in a European jurisdiction using a VPN. I then visited the pages and interacted with the CMPs as a first-time user, and compared the resulting consent strings. This led me to conclude that these odd consent strings are created by a user interacting with the CMP just enough to reach its “Privacy Manager” view and then saving and exiting with the default settings unchanged. As a typical impatient internet user, I did this the first time I encountered this UI configuration. I assumed, because of the initial view you will see below, that “Reject All” was already the default across the “Privacy Manager”, and I accepted the settings as they were, only to be surprised by the resulting consent string.

The Dark Pattern in the UI

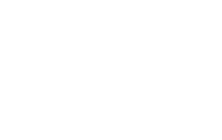

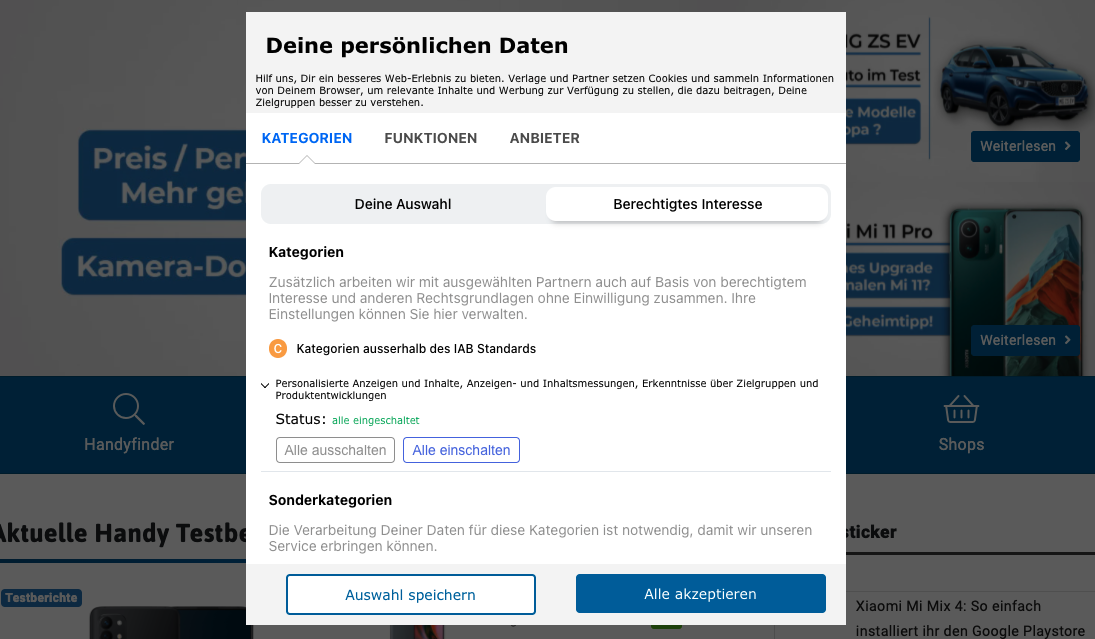

The screenshot below is an example of the first view that might be misleading for the average user. The toggle is set by default to “User Consent” and the “Reject All” option is selected by default, even showing a “Rejected All” notice in red to highlight the selected option for the user. A user, seeing this default, might reasonably assume that “Reject All” is the default selection for all sections and that they can safely and quickly select “Save & Exit” without making any changes, thinking that they will not be tracked.

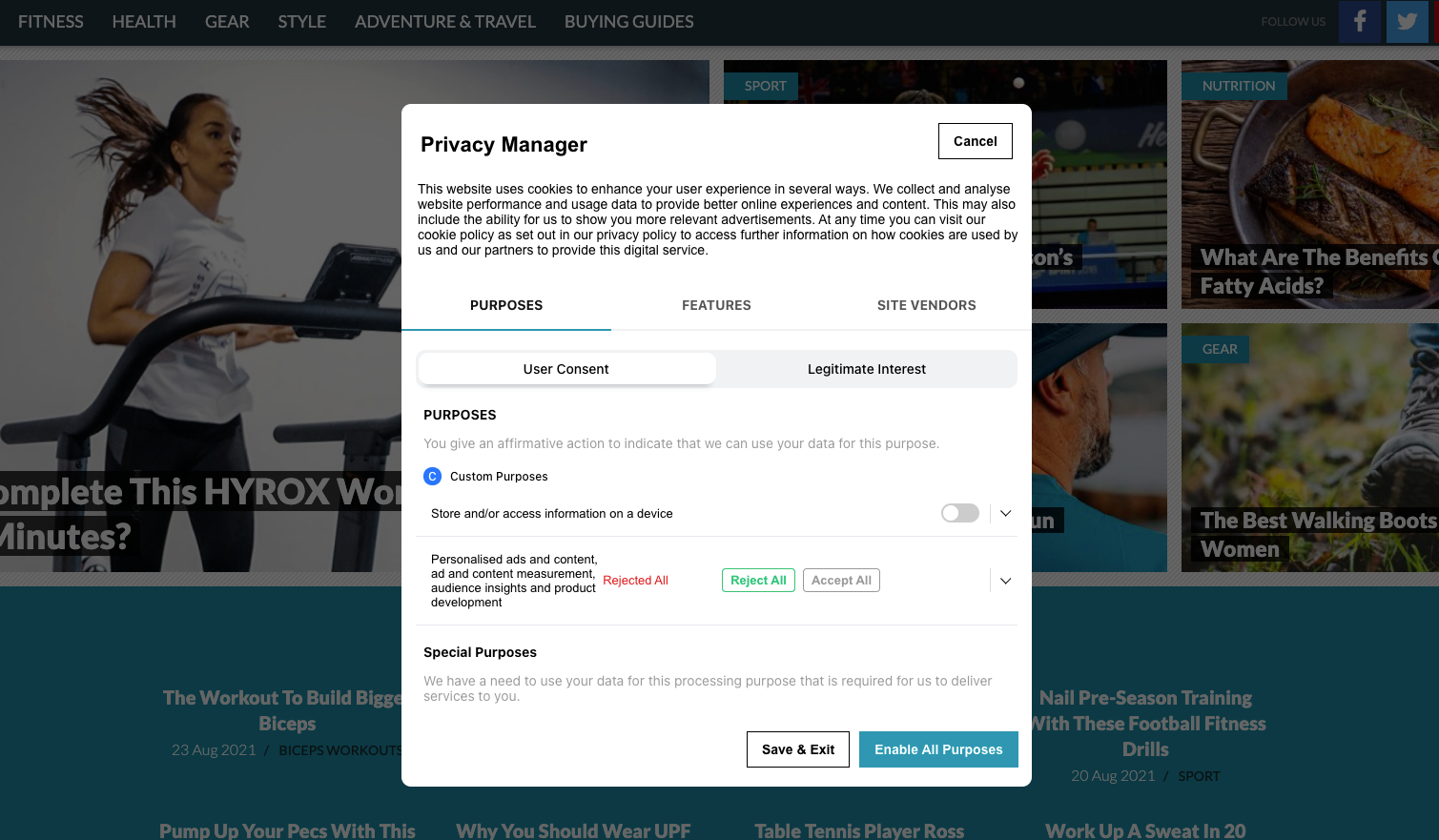

However, what makes this user experience and pattern so counterintuitive is that the default selection in the “Legitimate Interest” section, shown in the screenshot below, is the opposite. The default is actually set to “Accept All”, providing vendors with a legal basis to track users for all declared purposes, even if the user rejected those same purposes in the “User Consents” section. The user would only see and change this selection if it occurred to them to click and toggle to the “Legitimate Interest” section, which they might not even have noticed.

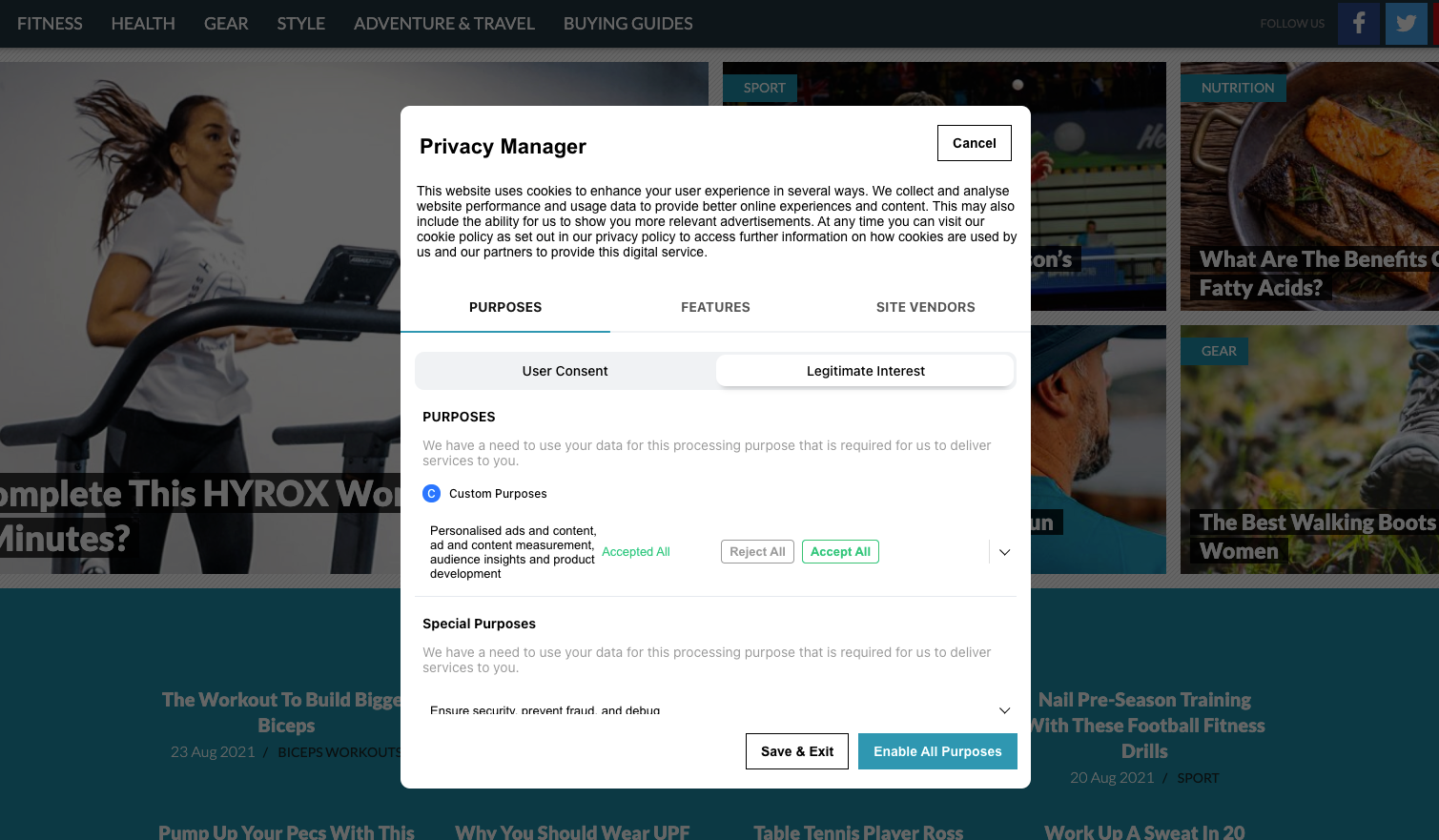

This exact CMP configuration can be found on several websites; you can even see a slightly different German language example of this interaction design pattern here:

Legitimate Interest and Dark Patterns

Legitimate Interest is a valid legal basis for processing data under the GDPR according to Recital 47, and it is enough to have Legitimate Interest alone even if a user has not given consent. A user does, however, have a right to object (Recitals 69-70) to the vendor’s declaration of Legitimate Interest. The concern here is not the use of Legitimate Interest, but that the interface through which it is accepted utilizes a dark pattern that subverts consumer expectations and prevents consumers from exercising their right to object.

Dark patterns are deceptive or confusing UX designs that influence consumers to act against their own interest or intentions. The term was first used in 2010 by UX Designer Harry Brignull of darkpatterns.org, who defines them as “tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to, like buying or signing up for something.” Utilizing dark patterns in a cookie banner visual design prevents a user from providing informed and deliberate consent. In this case, a user may intend to reject all legal bases for tracking but is potentially deceived by the counterintuitively different default settings between the “User Consent” section and the “Legitimate Interest” section, the latter of which is initially hidden by a toggle. Recitals 42 and 43 of the GDPR require meaningful, informed user consent, and regulators like CNIL have begun sanctioning companies for using dark patterns in their consent banners. European data enforcement platform noyb recently filed 422 GDPR complaints about cookie banners that utilize dark patterns to gain user consent, with ten different data protection authorities. Earlier this year the CCPA was amended to prohibit the use of dark patterns to prevent consumers from opting out of the sale of their personal information.

Conclusion

It stretches credulity that the average consumer has a sophisticated enough understanding of GDPR privacy regulations that they would reject all consents, but deliberately and knowingly accept that same level of tracking under the basis of Legitimate Interest. It is all too easy to imagine that a user like myself has just enough attention span to reject “User Consent” but not to click one level further to double check the settings in the “Legitimate Interest” section.

That being said, out of a sample of 16,000 TCF consent strings in our database (from a variety of CMP configurations), I found only 151 with this odd Legitimate Interest only result. The rest, for the most part, contained both Consent and Legitimate Interest, plausibly indicating a user who immediately clicked “Accept All” to dismiss the cookie banner rather than take the extra step to interact with its settings. Without this dark pattern, publishers and vendors are already getting consent the vast majority of the time, so it’s hard to argue that this tactic adds much value. In contrast, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) framework, which made objecting to tracking as simple as clicking the first button a user sees, has resulted in users "giving apps permission to track their behavior just 25% of the time".

This dark pattern is found in cookie banners used across several publications, in multiple languages, and its use adds liability to what would otherwise be a valid legal basis for tracking. Given how rarely users even interact with this part of the UI, it creates a completely avoidable and unnecessary risk for publishers and vendors alike. One simple mitigation would be changing the default in either section to match the other. I recognize that the logic behind the different default settings most likely reflects the opt-in vs. opt-out nature of these legal bases as laid out in regulations, but while that may be intuitive to publishers, it most likely will not be the bet user experience for consumers. A default of "Reject All" for both may be the most compliant option. Ultimately, the strongest mitigation for this issue would be publishers taking the time to understand the interface experience that the default settings of their CMP configuration create for users and adjusting any that lead to dark patterns such as this one.